Introduction

Encapsulation and Abstractions

The term encapsulation covers two closely related ideas:

- simplifying behavior

- hiding data

In this discussion, we’re using the first sense. We encapsulate behavior by identifying a task that needs to be done in our code and giving that task to a well-defined object or function. We call that object or function an abstraction.

Example: Making an HTTP request in python

import json

from urllib.request import urlopen

from urllib.parse import urlencode

params = dict(q='Sausages', format='json')

handle = urlopen('http://api.duckduckgo.com' + '?' + urlencode(params))

raw_text = handle.read().decode('utf8')

parsed = json.loads(raw_text)

results = parsed['RelatedTopics']

for r in results:

if 'Text' in r:

print(r['FirstURL'] + ' - ' + r['Text'])import requests

params = dict(q='Sausages', format='json')

parsed = requests.get('http://api.duckduckgo.com/', params=params).json()

results = parsed['RelatedTopics']

...Higher abstraction

import duckduckpy

for r in duckduckpy.query('Sausages').related_topics:

print(r.first_url, ' - ', r.text)Layering

- Encapsulation and abstraction help us by hiding details and protecting the consistency of our data, but we also need to pay attention to the ==interactions== between our objects and functions

- When one function, module, or object uses another, we say that the one ==depends on== the other

- In a big ball of mud, the dependencies are out of control

- Changing one node of the graph becomes difficult because it has the potential to affect many other parts of the system

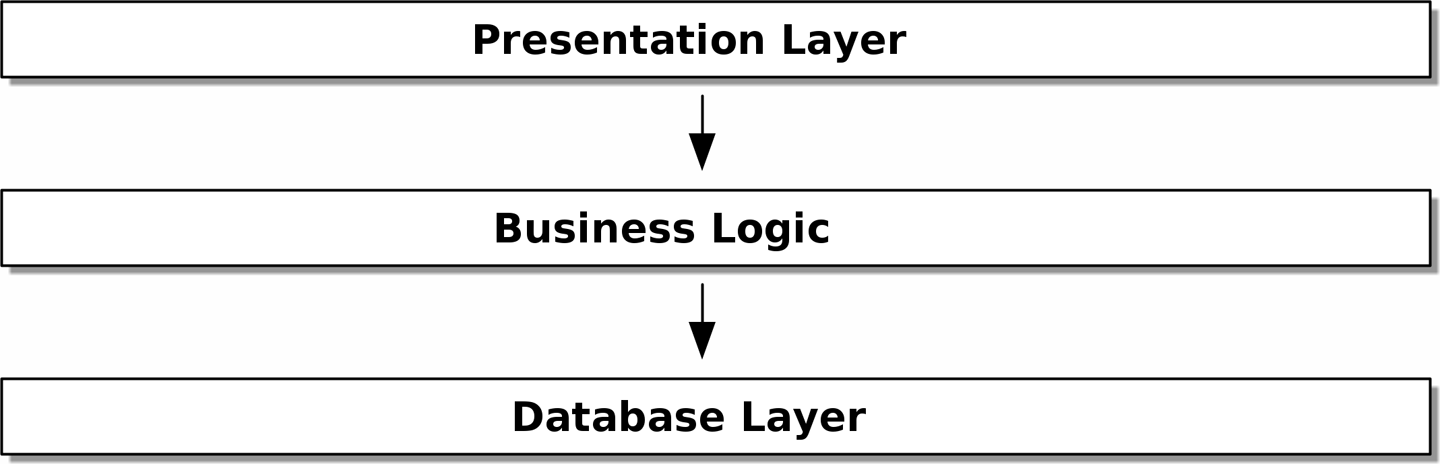

- Layered architecture is perhaps the most common pattern for building business software. In this model we have

-

user-interface components, which could be a web page, an API, or a command line; these user-interface components communicate with a

-

business logic layer that contains our business rules and our workflows;

-

and finally, we have a database layer that’s responsible for storing and retrieving data.

Layered architecture

-

Dependency Inversion Principle

**High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should

depend on abstractions.

**

| High-level modules (Business logic) | Low-level modules |

|---|---|

| Organization cares abouts | Organization doesn’t care |

| Bank ⇒ Trades and exchanges modules | If payroll runs on time, your business is unlikely to care whether that’s a cron job or a transient function running on Kubernetes. |

Important

We don’t want business logic changes to slow down because they are closely coupled to low-level infrastructure details. But, similarly, it is important to be able to change your infrastructure details when you need to (sharding a database), without needing to make changes to your business layer. Adding an abstraction between them (the famous extra layer of indirection) allows the two to change (more) independently of each other.

Abstractions should not depend on details. Instead, details should depend on abstractions.

1. Domain Modeling

The domain is a fancy way of saying the problem you’re trying to solve.

A model is a map of a process or phenomenon that captures a useful property.

Important

The domain model is the mental map that business owners have of their businesses. All business people have these mental maps—they’re how humans think about complex processes.

Dataclasses Are Great for Value Objects

An order line is uniquely identified by its order ID, SKU, and quantity; if we change one of those values, we now have a new line.

Notice that while an order has a reference that uniquely identifies it, a line does not.

Order_reference: 12345

Lines:

- sku: RED-CHAIR

qty: 25

- sku: BLU-CHAIR

qty: 25

- sku: GRN-CHAIR

qty: 25Important

Whenever we have a business concept that has data but no identity, we often choose to represent it using the Value Object pattern. A value object is any domain object that is uniquely identified by the data it holds; we usually make them immutable

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class OrderLine:

orderid: OrderReference

sku: ProductReference

qty: QuantityWhat’s the difference with Entities?

We use the term entity to describe a domain object that has long-lived identity. On the previous page, we introduced a Name class as a value object.

If we take the name Harry Percival and change one letter, we have the new Name object Barry Percival.

Important

Entities, unlike values, have identity equality. We can change their values, and they are still recognizably the same thing.

Batches, in our example, are entities. We can allocate lines to a batch, or change the date that we expect it to arrive, and it will still be the same entity.

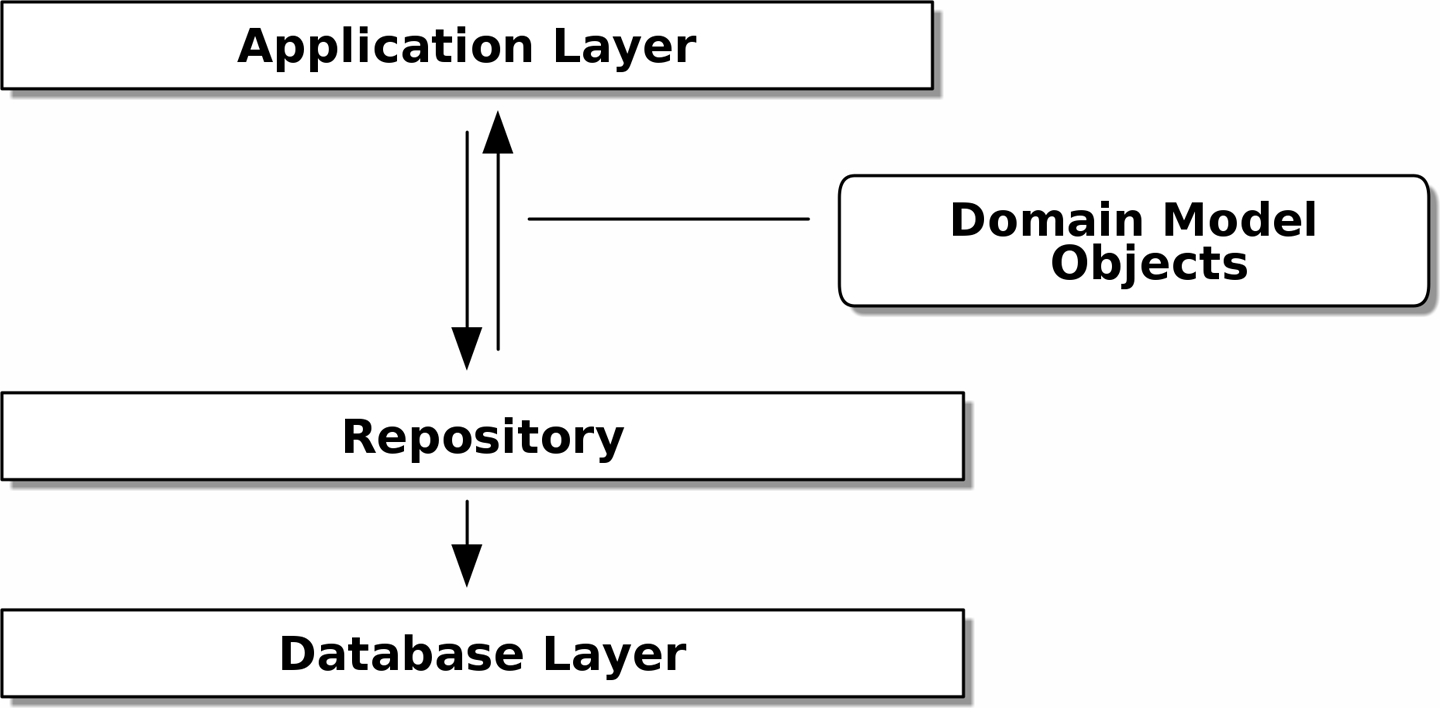

2. Repository Pattern

If you’ve been reading about architectural patterns, you may be asking yourself questions like this:

Is this ports and adapters? Or is it hexagonal architecture? Is that the same as onion architecture? What about the clean architecture? What’s a port, and what’s an adapter? Why do you people have so many words for the same thing?

Although some people like to nitpick over the differences, all these are pretty much names for the same thing, and they all boil down to the dependency inversion principle:

Important

high-level modules (the domain) should not depend on low-level ones (the infrastructure)

Layers, Onions, Ports, Adapters: it's all the same

If you apply the Dependency Inversion Principle to Layered Architecture, you end up with Ports and Adapters.

https://oreil.ly/LpFS9

Pros

-

We have a simple interface between persistent storage and our domain model.

-

It’s easy to make a fake version of the repository for unit testing, or to

swap out different storage solutions, because we’ve fully decoupled the model

from infrastructure concerns. -

Writing the domain model before thinking about persistence helps us focus on

the business problem at hand.

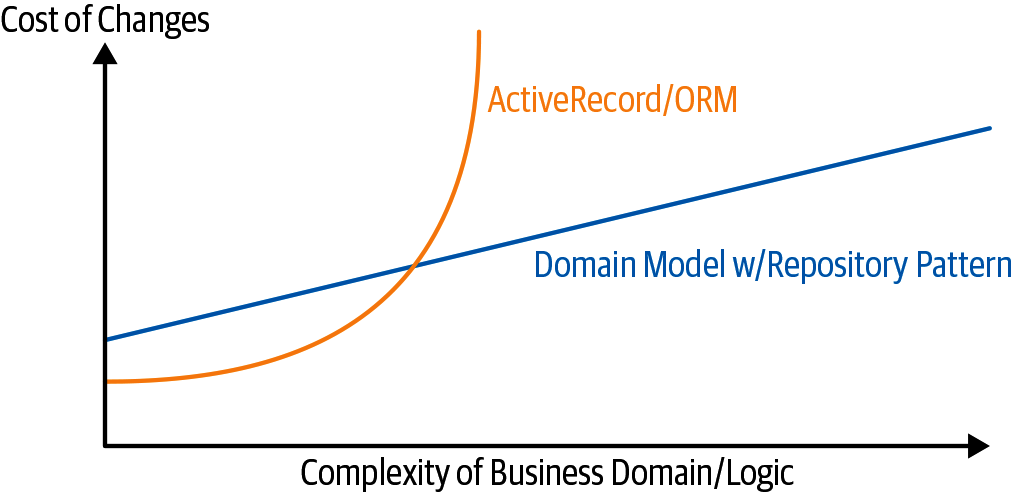

Cons

-

An ORM already buys you some decoupling. Changing foreign keys might be hard,

but it should be pretty easy to swap between MySQL and Postgres if you

ever need to. -

Maintaining ORM mappings by hand requires extra work and extra code.

-

Any extra layer of indirection always increases maintenance costs and

adds a “WTF factor” for Python programmers who’ve never seen the Repository pattern

before.

Recap

Apply dependency inversion to your ORM

Our domain model should be free of infrastructure concerns, so your ORM should import your model, and not the other way around.

The Repository pattern is a simple abstraction around permanent storage

The repository gives you the illusion of a collection of in-memory objects. It makes it easy to create a FakeRepository for testing and to swap fundamental details of your infrastructure without disrupting your core application.

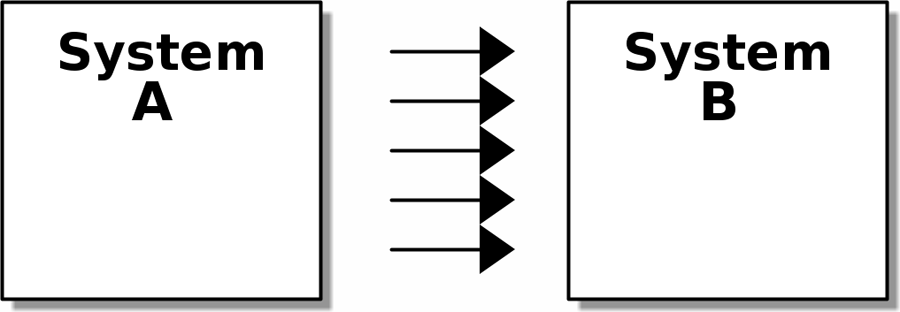

3. On Coupling and Abstractions

High Coupling: If we need to change system B, there’s a good change that that will affect A

The abstraction serves to protect us from change by hiding away the complexity of system B. We can change the arrows on the right without changing the ones on the left.

Important

Instead of saying, “Given this actual filesystem, when I run my function,check what actions have happened,” we say, “Given this abstraction of a filesystem,what abstraction of filesystem actions will happen?”

From https://www.destroyallsoftware.com/screencasts/catalog/functional-core-imperative-shell:

Purely functional code makes some things easier to understand: because values don’t change, you can call functions and know that only their return value matters—they don’t change anything outside themselves. But this makes many real-world applications difficult: how do you write to a database, or to the screen?

Mocks Versus Fakes; Classic-Style Versus London-School TDD

Here’s a short and somewhat simplistic definition of the difference between

mocks and fakes:

- Mocks are used to verify how something gets used; they have methods like

assert_called_once_with(). They’re associated with London-school TDD. - Fakes are working implementations of the thing they’re replacing, but they’re designed or use only in tests. They wouldn’t work “in real life”; our in-memory repository is a good example. But you can use them to make assertions about the end state of a system rather than the behaviors along the way, so they’re associated with classic-style TDD.

4: Our First Use Case: Flask API and Service Layer

Goal

Introducing a Service Layer, and Using FakeRepository to Unit Test It

Important

If we look at what our Flask app is doing, there’s quite a lot of what wemight call orchestration—fetching stuff out of our repository, validatingour input against database state, handling errors, and committing in thehappy path. Most of these things don’t have anything to do with having aweb API endpoint (you’d need them if you were building a CLI, for example

Depend on Abstractions

Notice one more thing about our service-layer function:

def allocate(line: OrderLine, repo: AbstractRepository, session) -> str:It depends on a repository. We’ve chosen to make the dependency explicit, and we’ve used the type hint to say that we depend on AbstractRepository. This means it’ll work both when the tests give it a FakeRepository and when the Flask app gives it a SqlAlchemyRepository.

Why Is Everything Called a Service?

We’re using two things called a service in this chapter.

Application service (our service layer)

Its job is to handle requests from the outside world and to orchestrate an operation

- Get some data from the database

- Update the domain model

- Persist any changes

Domain service

This is the name for a piece of

logic that belongs in the domain model but doesn’t sit naturally inside a stateful entity or value object

. For example, if you were building a shopping cart application, you might choose to build taxation rules as a domain service. Calculating tax is a separate job from updating the cart, and it’s an important part of the model, but it doesn’t seem right to have a persisted entity for

the job. Instead a stateless TaxCalculator class or a

calcu4late_tax function

can do the job.

Wrap up

- Our Flask API endpoints become very thin and easy to write: their only responsibility is doing “web stuff,” such as parsing JSON and producing the right HTTP codes for happy or unhappy cases.

- We’ve defined a clear API for our domain, a set of use cases or entrypoints that can be used by any adapter without needing to know anything about our domain model classes—whether that’s an API, a CLI (see [appendix_csvs]), or the tests!

- And our test pyramid is looking good—the bulk of our tests are fast unit tests, with just the bare minimum of E2E and integration tests.

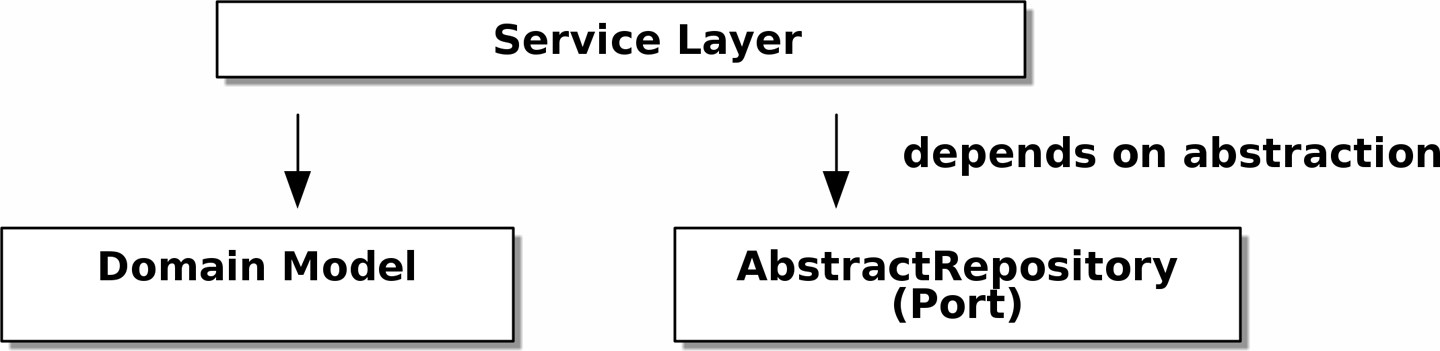

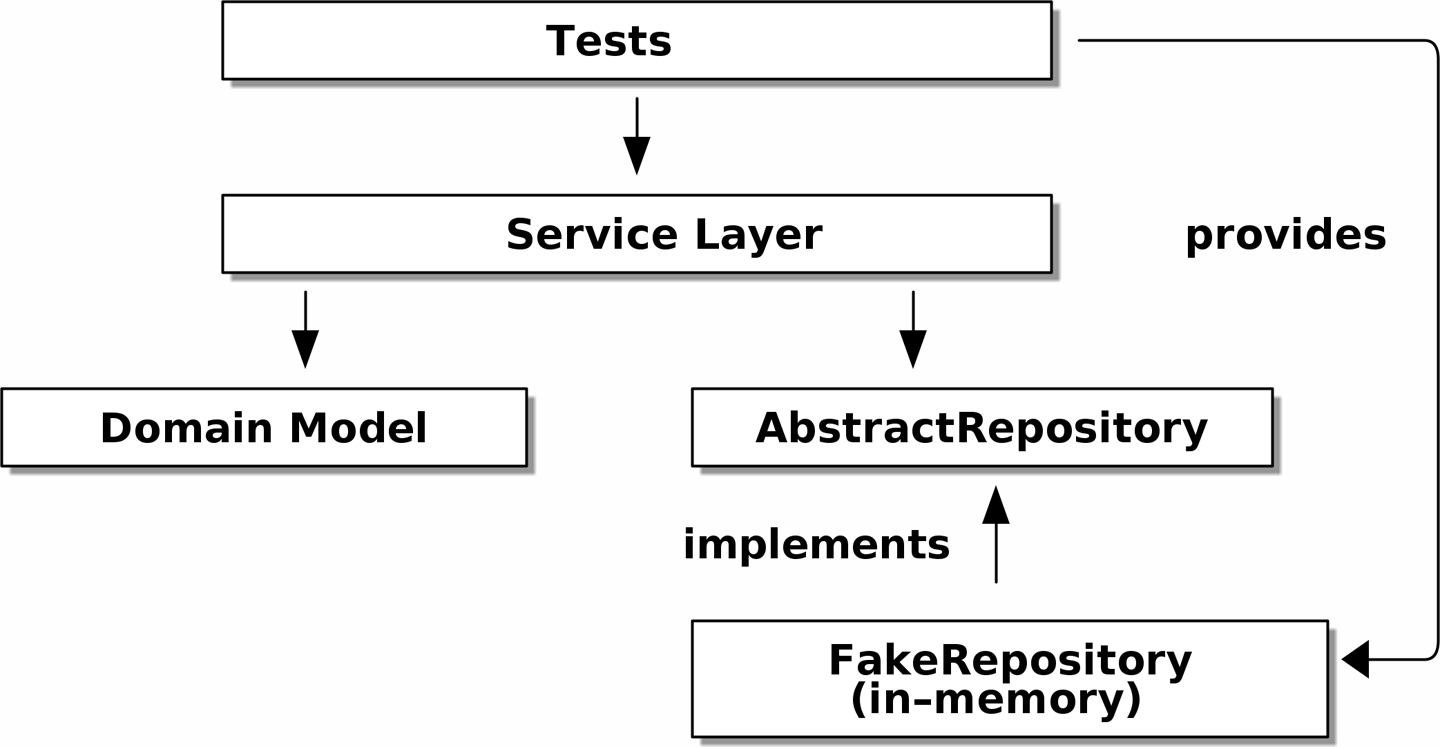

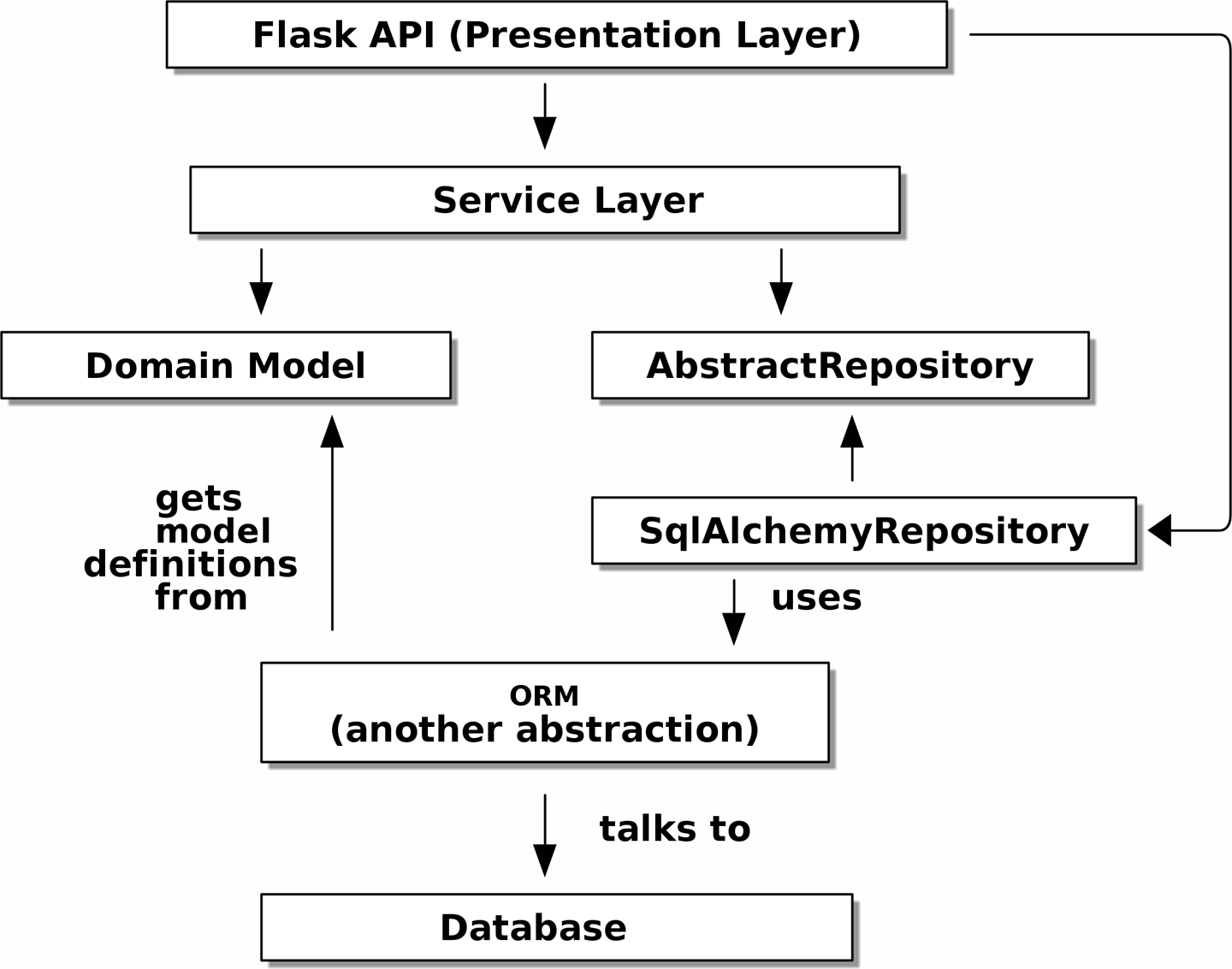

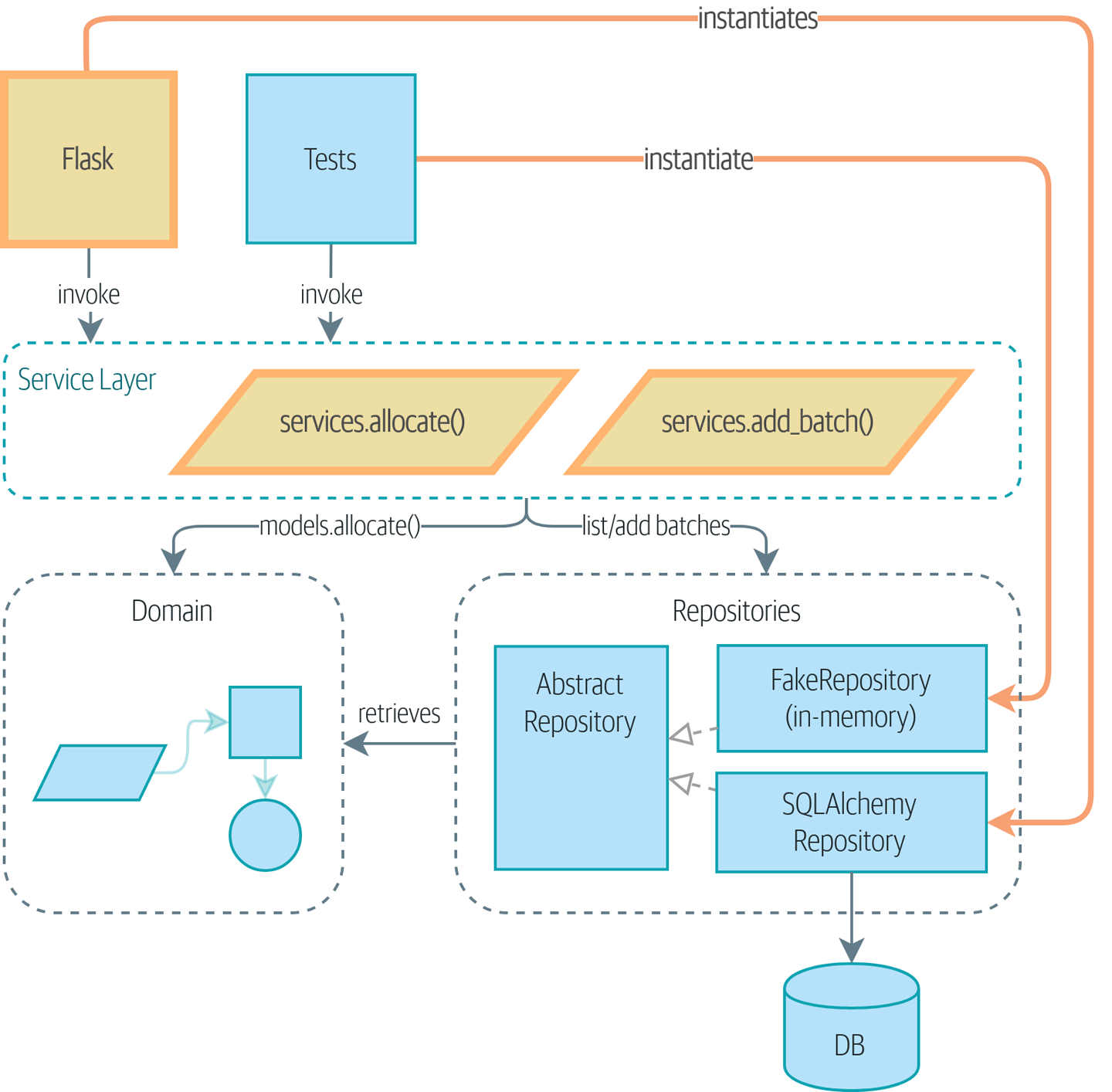

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) in action

Abstract dependencies of the service layer shows the dependencies of our service layer: the domain model and AbstractRepository (the port, in ports and adapters terminology).

When we run the tests, Tests provide an implementation of the abstract dependency shows how we implement the abstract dependencies by using FakeRepository (the

adapter).

And when we actually run our app, we swap in the “real” dependency shown in

Service Layer - Tradeoffs

| ==Pros | Cons |

| We have a single place to capture all the use cases for our applicati | If your app is purely a web app, your controllers/view functions can be the single place to capture all the use cases. |

| We’ve placed our clever domain logic behind an API, which leaves us free to refac | It’s yet another layer of abstraction. |

| We have cleanly separated “stuff that talks HTTP” from “stuff that talks allocat | Putting too much logic into the service layer can lead to the Anemic Domain antipattern. It’s better to introduce this layer after you spot orchestration logic creeping into your controllers. When combined with the Repository pattern and FakeRepository, we have a nice way of writing tests at a higher level than the domain layer; we can test more of our workflow without needing to use integration tests. tests |

5. TDD

Important

Every line of code that we put in a test is like a blob of glue, holding the system in a particular shape. The more low-level tests we have, the harder it will be to change things.

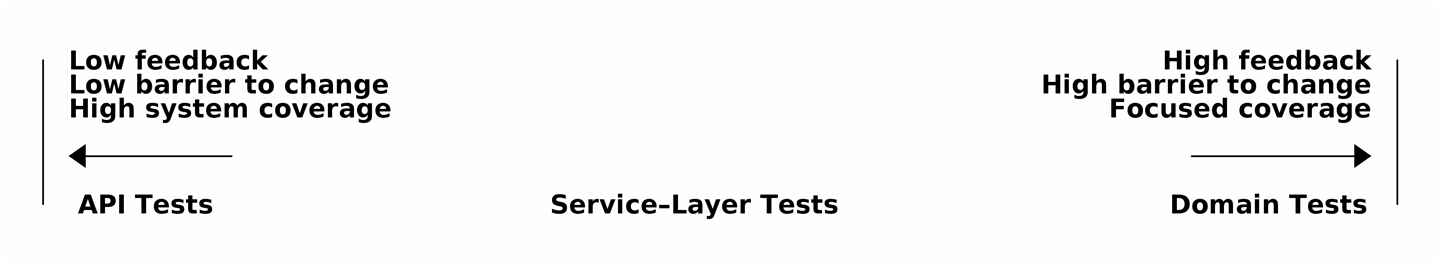

Básicamente si escribimos tests contra los domain models nos metemos más deep en la implementación. Esto nos ata al dominio y cuando éste cambie, nuestros tests también lo harán.

Por el contrario, los API tests son menos específicos (no tienen idea de la implementación, es el famoso “testear contra la interfaz”) y cubren más sobre el funcionamiento general del sistema. La ventaja es que aunque nuestros modelos de dominio cambien, los tests deberían seguir siendo similares. (Low coupling)

Important

In general, if you find yourself needing to do domain-layer stuff directly in your service-layer tests, it may be an indication that your service layer is incomplete.

Recap: Rules of Thumb for Different Types of Test

Aim for one end-to-end test per feature

This might be written against an HTTP API, for example. The objective is to demonstrate that the feature works, and that all the moving parts are glued together correctly.

Write the bulk of your tests against the service layer

These edge-to-edge tests offer a good trade-off between coverage, runtime, and efficiency. Each test tends to cover one code path of a feature and use fakes for I/O. This is the place to exhaustively cover all the edge cases and the ins and outs of your business logic.

Maintain a small core of tests written against your domain model

These tests have highly focused coverage and are more brittle, but they have the highest feedback. Don’t be afraid to delete these tests if the functionality is later covered by tests at the service layer.

Error handling counts as a feature

Ideally, your application will be structured such that all errors that bubble up to your entrypoints (e.g., Flask) are handled in the same way. This means you need to test only the happy path for each feature, and to reserve one end-to-end test for all unhappy paths (and many unhappy path unit tests, of course).

6. Unit of work

Important

If the Repository pattern is our abstraction over the idea of persistent storage, the Unit of Work (UoW) pattern is our abstraction over the idea of atomic operations. It will allow us to finally and fully decouple our service layer from the data layer.

Chapter 07 - Aggregates and consistency boundaries Chapter 08 - Events and the Message Bus Chapter 09 - Going to Town on the Message Bus Chapter 10 - Commands Chapter 11 - Event driven architecture Chapter 12 - CQRS Chapter 13 - DI and Bootstrap Cosmic Python - Epilogue

Next ideas

- Integrar con https://svcs.hynek.me/en/stable/

- Hacer la versión FastAPI

- Cosmic Django + Signals (Django 6.0 tasks)